The Brussels II Regulation 2003

Jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility

Basic system for jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility

Compared to its forerunner, the Regulation of 2001, the Brussels II Regulation 2003 sets up a complete basic system of jurisdiction for judgments on parental responsibility aimed at avoiding conflicts of competence. The rules have to a large extent been inspired by the corresponding rules of the 1996 Hague Convention on jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition, enforcement and co-operation in respect of parental responsibility and measures for the protection of children (concluded October 19, 1996).

The fundamental principle of the Brussels II Regulation 2003 is that the most appropriate forum for matters of parental responsibility is the relevant court of the Member State of the habitual residence of the child (Article 8). The courts of this Member State therefore have jurisdiction over matters relating to parental responsibility. The basic ground of the child's habitual residence is qualified in certain cases of a change in the child's residence (lawful as in Article 9 or unlawful as in Article 10) or pursuant to an agreement between the holders of parental responsibility (Article 12) and a flexibility mechanism is also provided for by means of the possibility to transfer the legal proceeding to a court better placed to hear the case (Article 15). The aim is to attribute jurisdiction in all cases in a way that serves the best interests of the child. (EC Proposal 2002, Section 2). The Regulation determines merely the Member State whose courts have jurisdiction, but not the court which is competent within that Member State. This question is left to domestic procedural law.

The rules of the Brussels II Regulation 2003 on jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility apply irrespective of the child's habitual residence being within or outside the European Union. However, should the European Community decide for the ratification of the 1996 Hague Convention by its Member States, the rules on jurisdiction set out in the 1996 Hague Convention would take precedence over Community rules where the child concerned is not resident within the European Union and is resident in a Contracting Party to the 1996 Hague Convention that is not a EU Member State.

With regard to jurisdiction over matters of child abduction the Brussels II Regulation 2003 presents, in Articles 10, 11, 40, 42 and 55, a set of individual provisions, that orders which EU Member State’s courts are allowed to rule in these cases. The Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the civil aspects of international child abduction (the 1980 Hague Convention), which has been ratified by all EU Member States, will continue to apply in the relations between EU Member States. However, the 1980 Hague Convention is supplemented by certain provisions of the Brussels II Regulation, which come into play in cases of child abduction between EU Member States. The rules of the Brussels II Regulation thus in fact prevail over the rules of the 1980 Hague Convention in relations between EU Member States in matters covered by the Regulation, while the provisions of the 1980 Hague Convention keep their relevance, even between EU Member States, in so far the Brussels II Regulation might not deal with a particular subject with respect to child abduction.

In contrast to the former Regulation of 2001, the present Brussels II Regulation 2003 applies to all decisions issued by a court of a Member State in matters of parental responsibility, including the attribution, exercise, delegation, restriction and termination of as well as rights of custody and rights of access. (Article 1(1)(b) and Recital 5 BR II 2003). The former Regulation applied to decisions on parental responsibility only to the extent that they were issued in the context of a matrimonial proceeding and concerned children common to both spouses. In order to ensure equality for all children, the scope of the new Regulation extends to cover all decisions on parental responsibility, regardless of whether the parents are or were married and whether the parties to the proceedings are or are not both biological parents of the child in question. The term ‘parental responsibility’ must be construed widely because a narrow construction of the term would frustrate this important objective of Brussels II 2003.

The Regulation is not confined to court judgments (Article 2(1) and (4) BR II 2003). It applies to court judgments, whatever the judgment may be called (decree, order, decision etc.). However, it is not limited to decisions issued by courts, but applies to any decision pronounced by an authority having jurisdiction in matters falling under the Regulation (e.g. social authorities) (Practice Guide 2005, p. 10).

The Brussels II Regulation 2003, however, does not prevent courts from taking provisional measures in urgent cases, even with reference to parental responsibility matters. Article 20 BR II 2003 enables a court to take provisional, including protective, measures in accordance with its national law in respect of a child situated on its territory even if a court of another Member State has jurisdiction as to the substance of the application. The measure can be taken by a court or by an authority having jurisdiction in matters falling within the scope of the Regulation (Article 2(1)). A welfare authority or a youth authority may, for instance, be competent to take provisional measures under national law. Article 20 is not a rule which confers jurisdiction. Consequently, the provisional measures cease to have effect when the competent court has taken the measures it considers appropriate (Practice Guide 2005, p. 12).

| Example: |

General jurisdiction in matters of parental responsibility

(Article 8)

Again, the Brussels II Regulation 2003 issues in Article 8 a general rule on jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility (habitual resident of the child), which is followed directly by a number of exceptions to this rule (Articles 9, 10, 12 and 13), indicating that jurisdiction may lie with the courts of a Member State in which the child is not habitually resident.

Article 8 (1) BR II 2003 presents the rule of general jurisdiction: The courts of a Member State shall have jurisdiction in matters of parental responsibility over a child who is habitually resident in that Member State at the time the court is seised. Therefore the Member State were one or both parents, the respondent parent or another holder of access rights resides, is not important. Article 8(2) BR II 2003, however, stresses out that the rule to determine jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility is subject to the provisions of Articles 9, 10 and 12 BR II 2003.

As in the 1996 Hague Convention, jurisdiction is based in the first place on the child's habitual residence. This also means that, where a child's habitual residence changes, the courts of the Member State of his or her new habitual residence shall have jurisdiction. In line with customary practice within the Hague Conference where the concept of 'habitual residence' has been developed, the term is not defined, but is instead a question of fact to be appreciated by the judge in each case.

‘The concept of “habitual residence”, which is increasingly used in international instruments, is not defined by the Regulation, but has to be determined by the judge in each case on the basis of factual elements. The meaning of the term should be interpreted in accordance with the objectives and purposes of the Regulation. It must be emphasised that this does not refer to any concept of habitual residence under national law, but an “autonomous” notion of Community law. If a child moves from one Member State to another, the acquisition of habitual residence in the new Member State, should, in principle, coincide with the “loss” of habitual residence in the former Member State. Consideration by the judge on a case-by-case basis implies that whilst the adjective “habitual” tends to indicate a certain duration, it should not be excluded that a child might acquire habitual residence in a Member State the very day of the arrival, depending on the factual elements of the concrete case.

The question of jurisdiction is determined at the time the court is seised. Once a competent court is seised, in principle it retains jurisdiction even if the child acquires habitual residence in another Member State during the course of the court proceeding (principle of “perpetuatio fori”). A change of habitual residence of the child while the proceeding is pending does therefore not itself entail a change of jurisdiction. However, if it is in the best interests of the child, Article 15 provides for the possible transfer of the case, subject to certain conditions, to a court of the Member State to which the child has moved (see chapter III). If a child’s habitual residence changes as a result of a wrongful removal or retention, jurisdiction may only shift under very strict conditions’ (Practice Guide 2005, p. 13-14).

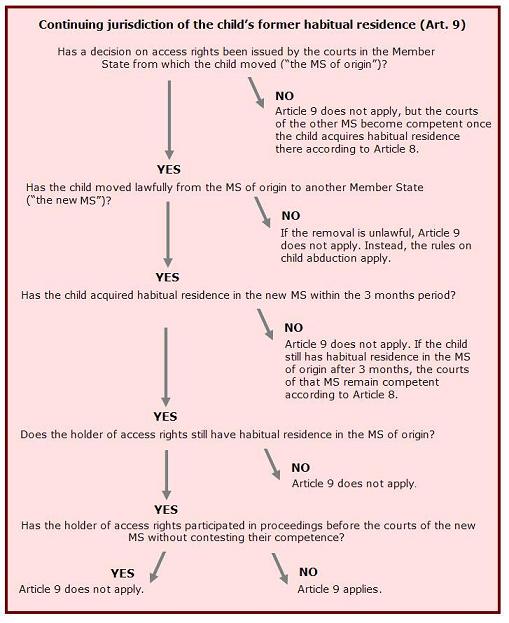

Continuing jurisdiction of the child's former habitual residence (Article

9)

Jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility depends, looking at the general rule of Article 8 BR II 2003, on the habitual residence of the child, and not of that of its parents or even the respondent parent. Decisive is the habitual residence of the child at the moment on which the lawsuit or legal request is brought before a court of one of the Member States. This has to be the court of the Member State where the child in question at that time actually has its regular home.

But it’s conceivable that the child, soon after the legal proceeding has brought before the court of the authorised Member State, moves to another country. The Brussels II Regulation 2003 takes this possibility into account and differentiates in this respect between a lawful and an unlawful relocation of the child. An unlawful relocation of the child to another country, is regarded as a child abduction. The Brussels II Regulation 2003 gives different rules for this in Articles 10, 11, 40, 42, 55.

It’s also possible that the child moves lawfully to another country after the lawsuit has been introduced to the court of a Member State. Articles 9, 12 and 13 BR II 2003 set out the exceptions to the general rule of Article 8 BE II 2003, i.e. where jurisdiction may lie with the courts of a Member State in which the child is not habitually resident.

| Article

9 |

Article 9 applies in certain cases of relocation, that is of a lawful change of residence of a child, to allow jurisdiction to remain for some time with the Member State of the former residence of the child. The conditions that must be met for the continuing jurisdiction of the courts of the Member State of the child's former residence that have already issued a judgment on parental responsibility are that the child has only recently moved to his or her new residence while one of the holders of parental responsibility continues to reside in the Member State of the former residence of the child. Thus the modification of its earlier judgment to take into account the child's relocation is made by the court that is closest to the child, which allows for some continuity without nonetheless touching on the definition of the term 'habitual residence' (Proposal 2002: Article 11 [now 9])

The Practice Guide 2005 gives the following comment on Article 9.

‘When a child moves from one Member State to another, it is often necessary to review the access rights, or other contact arrangements, to adapt them to the new circumstances.

Article 9 is an innovative rule which encourages holders of parental responsibility to agree upon the necessary adjustments of access rights before the move and, if this proves impossible, to apply to the competent court to resolve the dispute. It does not in any way prevent a person from moving within the European Community, but provides a guarantee that the person who can no longer exercise access rights as before does not have to seise the courts of the new Member State, but can apply for an appropriate adjustment of access rights before the court that granted them during a period of three months following the move. The courts of the new Member State do not have jurisdiction in matters of access rights during this period.

Article 9 is subject to the following conditions:

- The courts of the Member State of origin must have issued a decision on access rights.

Article 9 applies only to the situation where a holder of access rights wishes to modify a previous decision on access rights. If no decision on access rights has been issued by the courts in the Member State of origin, Article 9 does not apply, but the other jurisdiction rules come into play. The courts of the new Member State would have jurisdiction pursuant to Article 8 to decide on matters of access rights once the child acquires habitual residence in that State.

- It applies only to “lawful” moves.

It must be determined whether, according to any judicial decision or the law applied in the Member State of origin (including its rules on private international law), the holder of parental responsibility is allowed to move with the child to another Member State without the consent of the other holder of parental responsibility. If the removal is unlawful, Article 9 does not apply, but Article 10 comes into play (see chapter VII). If, on the other hand, the unilateral decision to change the child’s habitual residence is lawful, Article 9 applies if the conditions set out below are fulfilled.

- It applies only during the three-month period following the child’s move.

The three-month period is to be calculated from the date the child physically moved from the Member State of origin. The date of the move should not be confused with the date when the child acquires habitual residence in the new Member State. If a court in the Member State of origin is seised after the expiry of the three-month period from the date of the move, it does not have jurisdiction under Article 9.

- The child must have acquired habitual residence in the new Member State during the three-month period.

Article 9 applies only if the child has acquired habitual residence in the new Member State during the three-month period. If the child has not acquired habitual residence within that period, the courts of the Member State of origin would, in principle, retain jurisdiction pursuant to Article 8.

- The holder of access rights must still have habitual residence in the Member State of origin.

If the holder of access rights has ceased to be habitually resident in the Member State of origin, Article 9 does not apply, but the courts of the new Member State become competent once the child has acquired habitual residence there.

- The holder of access rights must not have accepted the change of jurisdiction.

Since the aim of this provision is to guarantee that the holder of access rights can seise the courts of his or her Member State, Article 9 does not apply if he or she is prepared to accept that jurisdiction shifts to the courts of the new Member State. Hence, if the holder of access rights participates in proceedings concerning access rights before a court in the new Member State without contesting the jurisdiction of that court, Article 9 does not apply and the court of the new Member State acquires jurisdiction (paragraph 2). Similarly, Article 9 does not prevent the holder of access rights from seising the courts of the new Member State for review of the question of access rights.

- does not prevent the courts of the new Member State from deciding on matters other than access rights.

Article 9 deals only with jurisdiction to rule on access rights, but does not apply to other matters of parental responsibility, e.g. custody rights. Article 9 does not therefore prevent a holder of parental responsibility who has moved with the child to another Member State from seising the courts of that Member State on the question of custody rights during the three-month period following the move (Practice Guide 2005, p. 13 and 14).

See also the scheme of the Practice Guide

Prorogation of jurisdiction (Article 12)

The Brussels II Regulation 2003 introduces in Article 12 a limited possibility to seise a court of a Member State in which the child is not habitually resident, either (a) because the matter is connected with a pending divorce proceeding, or (b) because the child has a substantial connection with that Member State. Article 12 BR 2003 covers therefore two situations in which the courts of a Member State have jurisdiction over matters concerning parental responsibility, although the child has not its habitual residence there, so these courts cannot ground their jurisdiction on the general rule of Article 8 BR II 2003. First, the spouses may accept the jurisdiction of the divorce court to decide also on parental responsibility over their common children (Article 12(1)(2) BR II 2003). Second, Article 12(3) BR II 2003 allows for an agreement among all holders of parental responsibility to bring the case before the courts of a Member State with which the child has a substantial connection.

In Article 12 (1), the terms ‘Article 3’ are replaced by the terms ‘Articles 3 and 3a’. This amendment, however, is not yet in force. It ensures that a divorce court chosen by the spouses pursuant to Article 3a has jurisdiction also in matters of parental responsibility connected with the divorce application provided the conditions set out in Article 12 are met, in particular that the jurisdiction is in the best interests of the child. [Explanatory Memorandum COM) (2006) final]

(a) Derived jurisdiction because of a connection with

a matrimonial proceeding (Article 12(1)(2)).

Article 12(1)(2) BR II 2003 only applies when a Member State, which courts have jurisdiction over matrimonial matters relating to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment, and which courts are actually considering such a case, is not the State where the child has its habitual residence. Then from Article 12(1)(2) follows that, provided certain conditions are met, the Member State where the lawsuit with respect to the divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment is pending, also has jurisdiction over any matter relating to parental responsibility connected with that lawsuit, although the child concerned is not living in this Member State. This applies whether or not the child is the child of both spouses.

‘It needs to be made clear that in no case does that provision [Article 12 BR II 2003] mean that it must be the same authorities in the State concerned who rule on the matrimonial issue and on the parental responsibility: the rule is intended only to establish that the authorities deciding on both matters are authorities of the same State. In practice, they will be the same authorities in some States and separate authorities in others. For the purposes of the [Regulation], the only point of interest is that they be authorities of the same Member State, with due regard for the internal distribution of competence’ (Borras (1998) C 221/40).

The Member State of the divorce court has also jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility with regard to a child living in another State when the following conditions are met:

- At least one of the spouses has parental responsibility in relation to the child.

- The divorce court should determine whether, at the time the court is seised, all holders of parental responsibility accept the jurisdiction of the divorce court, whether by formal acceptance or unequivocal conduct.

- The jurisdiction of that court is in the superior interests of the

child.

Article 12 (4) BR II 2003 specifies in which circumstances jurisdiction under this Article shall be deemed to be in the “child’s best interest” when the child in question is habitually resident in a third State that is not a contracting State to the 1996 Hague Convention on Child Protection (see chapter XI). ‘Where the child has his or her habitual residence in the territory of a third State which is not a contracting party to the Hague Convention of 19 October 1996 on jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition, enforcement and cooperation in respect of parental responsibility and measures for the protection of children, jurisdiction under this Article shall be deemed to be in the child's interest, in particular if it is found impossible to hold proceedings in the third State in question’.

But the derived jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility of the Member State who’s court rules over a divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment, as set by Article 12(1) BR II 2003, can come to an end. One has to notice that this doesn’t mean that, when a lawsuit concerning parental responsibility is already filed with reference to Article 12(1) BR II 2003, this legal proceeding itself will end or that it is no longer possible to ask a Court of Appeal in that Member State to review the decision of a lower court. That’s not the case. It only means that the derived jurisdiction over parental responsibility of the Member State who’s court rule over the divorce ends, so as from that moment it is no longer possible to file a (new) lawsuit on parental responsibility at first instance at a court of a Member State of the divorce court on the ground of Article 12(1) BR II 2003. The from Article 12(1) derived jurisdiction of the Member State who’s court rules over a divorce, ceases as soon as one of the following events occur:

- the judgment allowing or refusing the application for divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment has become final;

- in those cases where proceedings in relation to parental responsibility are still pending on the date referred to in (a), a judgment in these proceedings has become final;

- the proceedings referred to in (a) and (b) have come to an end for another reason.

Subparagraph (a) deals with the basic assumption that the judgment allowing or refusing the application for divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment has become final, that is to say that no further appeal or review of any kind is possible. Once that happens, and without prejudice to subparagraph (b), Article 12(1) no longer applies. Parental responsibility will then have to be determined either by national law, including the Brussels II Regulation, or by the relevant international Conventions.

In addition to this well-known situation, and without prejudice to the residual rule in subparagraph (c), subparagraph (b) adds another situation where, on the date on which the judgment on the matrimonial proceedings becomes final, in the sense that such a judgment cannot be the subject of any sort of appeal, proceedings in relation to parental responsibility are still pending and provides that jurisdiction will not cease until a judgment in the responsibility proceedings has become final; in any event in this situation jurisdiction on parental responsibility may be exercised even if the judgment allowing or refusing the application for divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment has become final. ‘It was necessary to insert this provision in [the Brussels II Regulation] because it is conceivable that when different authorities within the same country are involved or in cases before the same authorities, the judgment on the matrimonial proceedings may be final at a time when the proceedings on parental responsibility have not yet come to an end. Jurisdiction on the parental responsibility therefore ceases on whichever of those two dates applies. It is therefore understood that proceedings on parental responsibility, once initiated, must continue until a final judgment is reached. The fact that the application relating to the marriage has been resolved may not prejudice the expectations created both for the parents and for the child that the parental responsibility proceedings will terminate in the Member State in which they began. Although not expressly stated, the intention is that there should be no perpetuatio jurisdiccionis but that proceedings on parental responsibility initiated in connection with matrimonial proceedings should not be interrupted’ (Borras (1998) C 221/41).

Subparagraph (c) deals with the residual or concluding situation where the proceedings have come to an end for another reason, for example because the application for divorce is withdrawn or one of the spouses dies (COM/99/0220 final - CNS 99/0110 / Official Journal C 247 E , 31/08/1999).

(b) Derived jurisdiction because the child has

a substantial connection with that Member State who’s court is seised

(Article 12(3)).

Article 12(3) BR II 2003 allows for an agreement among all holders of parental responsibility to bring the case before the courts of a Member State with which the child has a substantial connection. Such a connection may for instance be based on the habitual residence of one of the holders of parental responsibility or on the nationality of the child. This solution aims at promoting agreement, even if only on the court that should hear the case, also giving some flexibility to the holders of parental responsibility, while the court seized must find that assuming jurisdiction is in the best interests of the child.

Where there are no pending divorce proceedings, the courts of a Member State may have jurisdiction in matters of parental responsibility even if the child is not habitually resident in that Member State provided the following conditions are all met:

- The child has a substantial connection with the Member State in question, in particular because one of the holders of parental responsibility is habitually resident there or the child is a national of that State. These conditions are not exclusive, and it is possible to base the connection on other criteria.

- All parties to the proceedings accept the jurisdiction of that court explicitly or otherwise unequivocally at the time the court is seised (cf. the same requirement in situation 1).

- The jurisdiction is in the best interests of the child (as above in Article 12(1)(2)).

Jurisdiction based on the child's presence (Article

13)

If it proves impossible to determine the habitual residence of the child and Article 12 does not apply, Article 13 allows the court of a Member State to decide on matters of parental responsibility with regard to children who are at that time actually present in that Member State. This Article is subsidiary in relation to the jurisdictional bases in the preceding articles.

Paragraph 2 of Article 13 BR II 2003 provides for the jurisdiction of the Member State of the child's presence also in respect of refugee children.

Residual jurisdiction (Article 14)

The residual application of national rules of conflicts of law is foreseen where no court of a Member State has jurisdiction under the previous Articles. ‘Where no court of a Member State has jurisdiction pursuant to Articles 8 to 13, jurisdiction shall be determined, in each Member State, by the laws of that State’ (Article 14 BR II 2003). Such jurisdiction is termed 'residual' in view of its nature and the place it occupies in relation to the grounds of jurisdiction established by the Regulation. The importance of Article 13 BR II 2003 is mainly to achieve that a national decision, based on residual jurisdiction, benefits from the rules of the Brussels II Regulation for its recognition and enforcement in all other Member States.

Following the provision in Article 6 (exclusive nature of jurisdiction under Articles 3 to 5), Article 14 deals with arrangements existing in the national legal system which can be used only in the context of this Article. For some States, when one of the spouses resides in a non-member State and none of the jurisdictional criteria of the Regulation is met, jurisdiction should be determined in accordance with the law applicable in the Member State in question. To deal with that situation, the solution adopted is an assimilatory one whereby the applicant who is a national of a Member State who is habitually resident within the territory of another Member State may, like the nationals of that State, avail himself of the rules of jurisdiction applicable in that State. The prerequisite for applying that provision is that the respondent does not have his habitual residence in a Member State and is not a national of a Member State according to the criteria applicable to the case (COM/99/0220 final - CNS 99/0110 / Official Journal C 247 E , 31/08/1999)

‘46. This Article corresponds to the rules of exorbitant jurisdiction referred to in Articles 3 and 4 of the 1968 Brussels Convention. There are, however, differences between the two texts. The nature of the jurisdictions laid down in the aforementioned Articles renders unnecessary a provision such as Article 3 of the 1968 Brussels Convention. (Borras (1998) C 221/43)

47. (….) Such jurisdiction is termed ‘residual’ in view of its nature and the place it occupies in relation to the grounds of jurisdiction established by the Convention. That description was regarded as preferable to ‘extra-Community disputes’. In view of the function that that Article performs, like that of Article 4 of the Brussels Convention, contrary to the practice followed in Article 3 of the 1968 Brussels Convention, a list of these types of jurisdiction has not been included in this Article. Some States, like the Netherlands, have no jurisdiction in their internal legal system which can be defined as ‘residual’ for the purposes of Article 2 of the Convention.

Such jurisdiction does, however, exist in other national systems. Some examples are set out below.

In Germany, the rules of jurisdiction provided for in sections (1), (3) and (4) of Article 606a of the ‘Zivilprozessordnung’ could be described as residual; they provide that German courts have international jurisdiction when (1) one spouse is German or was German when the marriage took place; (2) one spouse is stateless and is habitually resident in Germany; or (3) one spouse is habitually resident in Germany, except where any judgment reached in their case could not be recognised in any of the States to which either spouse belonged.

In Finland, under Section 8 of the ‘Laki eräistä kansainvälisluontoisista perheoikeudellisista suhteista’/‘Lag angående vissa familjerättsliga förhållanden av internationell natur’ (International Family Relations Act) revised in 1987, Finnish courts will hear matrimonial cases even where neither spouse is habitually resident in Finland if the courts of the State of habitual residence of either of the spouses do not have jurisdiction or if application to the courts of the State of habitual residence would cause unreasonable difficulties and, furthermore, in the circumstances it would appear to be appropriate to assume jurisdiction (forum conveniens).

In Spain the only example would be one of the rules contained in Article 22(3) of the ‘Ley Orgánica del Poder Judicial’ (Law on the judicial system) of 1 July 1985 which allows the application to be made in Spain when the applicant is Spanish and is resident in Spain but does not meet any of the requirements in Article 2(1) of this Convention such as the express or tacit submission referred to in Article 22(2). Apart from that, all the other grounds for international jurisdiction in matrimonial matters which exist in Spanish law are contained in the Convention, these being that both spouses are habitually resident in Spain at the time of the application or that both spouses are of Spanish nationality, whatever their place of residence, provided that the application is made either jointly or with the agreement of the other spouse. (Borras (1998) C 221/43-44)

In France, Article 14 of the Civil Code would give French courts jurisdiction if the petitioner had French nationality.

In Ireland the courts would have jurisdiction in matters of annulment (Section 39 of the Family Law Act, 1995) divorce (Section 39 of the Family Law (Divorce) Act, 1996), and legal separation (Section 31 of the Judicial Separation and Family Law Reform Act, 1989), when either of the spouses is domiciled, for the purposes of Article 2(3), in the State on the date of institution of proceedings.

In Italy, the rules laid down in Articles 3, 4, 32 and 37 of Law 218 of 31 May 1995 on the reform of the Italian system of private international law are of this nature.

In the United Kingdom, a distinction has to be made between divorce, separation and annulment proceedings and custody orders relating to such proceedings. With regard to divorce, annulment and legal separation proceedings, this Article may cover grounds of jurisdiction based on the ‘domicile’ of either party in the United Kingdom at the time the application is made or on habitual residence for a year immediately preceding that date. In the case of divorce and separation proceedings, the Sheriff Courts in Scotland have jurisdiction if one party is either resident in the place for 40 days immediately prior to the submission of the application or has resided there for a period of at least 40 days ending not more than 40 days before that date and has no known residence in Scotland on that date. For custody orders contained in divorce, annulment and legal separation judgments, United Kingdom judicial bodies, including the Sheriff Courts in Scotland, will have jurisdiction, but if a court outwith the United Kingdom is conducting relevant proceedings, United Kingdom courts have a wide discretion to decline jurisdiction, provided that those proceedings continue and, in addition, that the proceedings continue before a judicial body that has jurisdiction under its national legislation. In the case of Sweden, the jurisdictional rules of Swedish courts for divorce matters are to be found in the ‘lag om vissa internationella rättsförhållanden rörande äktenskap och förmynderskap’ (Act on certain international legal relations concerning marriage and guardianship) 1904, as amended in 1973. As regards Article 7 of the Convention, Swedish courts have jurisdiction in matters of divorce if both spouses are Swedish citizens, if the petitioner is Swedish and is habitually resident in Sweden or has been so at any time since reaching the age of 18 or if, in other cases, the government gives its consent to the cases being heard in Sweden. The government can give its consent only if one of the spouses is Swedish or the petitioner cannot bring the case before the courts of the State of which he is a national’ (Borras (1998) C 221/44).

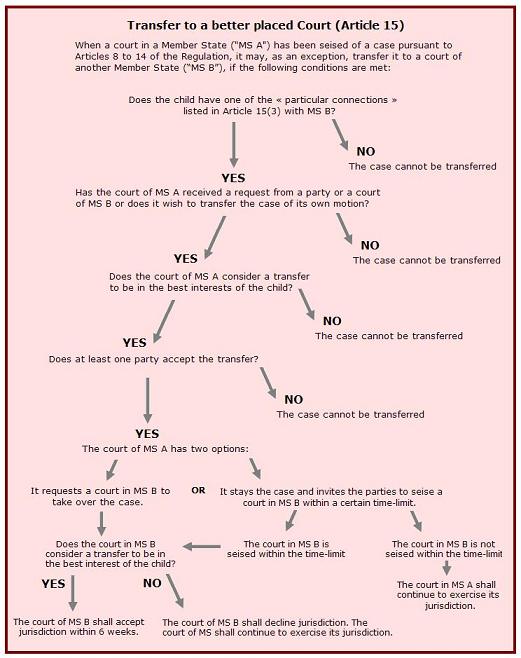

Transfer to a court better placed to hear the case

(Article 15)

The rules on jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility in Section 2 of the Brussels II Regulation 2003 have been structured with a view to putting into place a complete and rational system that serves the best interests of the child. Still, there may be situations (albeit exceptional) where the courts of another Member State would be better placed to hear the case. A provision that allows the transfer of a case thus has been included as Article 15 BR II 2003, both to recognize and to further promote the mutual trust that has been developing between Member States in the area of judicial cooperation. A similar mechanism for the transfer of cases is foreseen in the 1996 Hague Convention.

However, the system proposed here is less open-ended. It is emphasized that Article 15 should apply only in exceptional circumstances. The requisite connection to the Member State to which the case may be transferred is based on the child having a former habitual residence in that Member State, or the child being a national of that Member State, or one of the holders of parental responsibility having his or her habitual residence in that Member State or the child having property there. Moreover, the transfer must be requested by a holder of parental responsibility, and cannot therefore be made on the court's own initiative. An additional safeguard is the evaluation of the court proposing the transfer as well as the court accepting the transfer that this is in the best interests of the child.

The central authorities contribute towards facilitating communications between courts for purposes of this Article. At a later stage, a mechanism for direct court-to-court transfer may be envisaged; for the time being, however, the second court must be seized using normal procedures.

Practice Guide 2005: III. Transfer to a better placed court

‘Article 15

The Regulation contains an innovative rule which allows, by way of exception, that a court which is seised of a case transfers it to a court of another Member State if the latter is better placed to hear the case. The court may transfer the entire case or a specific part thereof.According to the general rule, jurisdiction lies with the courts of the Member State of the child’s habitual residence at the time the court was seised (Article 8). Therefore, jurisdiction does not shift automatically in a case where the child acquires habitual residence in another Member State during the court proceedings.

However there may be circumstances where, exceptionally, the court that has been seised (“the court of origin”) is not the best placed to hear the case. Article 15 allows in such circumstances that the court of origin may transfer the case to a court of another Member State provided this is in the best interests of the child.

Once a case has been transferred to the court of another Member State, it cannot be further transferred to a third court (Recital 13).1. In what circumstances is it possible to transfer a case?

The transfer is subject to the following conditions:

The child must have a “particular connection” with the other Member State.

Article 15(3) enumerates the five situations where such connection exists according to the Regulation:

• the child has acquired habitual residence there after the court of origin was seised; or

• the other Member State is the former habitual residence of the child; or

• it is the place of the child’s nationality; or

• it is the habitual residence of a holder of parental responsibility; or

• the child owns property in the other Member State and the case concerns measures for the protection of the child relating to the administration, conservation or disposal of this property.In addition, both courts must be convinced that a transfer is in the best interests of the child. The judges should co-operate to assess this on the basis of the “specific circumstances of the case”.

The transfer may take place:

• on application from a party or

• of the court’s own motion, if at least one of the parties agrees or

• on application of a court of another Member State, if at least one of the parties agrees.2. What procedure applies?

A court which is faced with a request for a transfer or which wants to transfer the case of its own motion has two options:

(a) It may stay the case and invite the parties to introduce a request before the court of the other Member State

or

(b) It may directly request the court of the other Member State to take over the case.In the former case, the court of origin shall set a time limit by which the parties shall seise the courts of the other Member State. If the parties do not seise such other court within the time limit, the case is not transferred and the court of origin shall continue to exercise its jurisdiction. The Regulation does not prescribe a specific time limit, but it should be sufficiently short to ensure that the transfer does not result in unnecessary delays to the detriment of the child and the parties. The court which has received the request for a transfer must decide, within six weeks of being seised, whether or not to accept the transfer. The relevant question should be whether, in the specific case, a transfer would be in the best interests of the child. The central authorities can play an important role by providing information to the judges on the situation in the other Member State. The assessment should be based on the principle of mutual trust and on the assumption that the courts of all Member States are in principle competent to deal

with a case.If the second court declines jurisdiction or, within six weeks of being seised, does not accept jurisdiction, the court of origin retains jurisdiction and must exercise it.

3. Certain practical aspects.

- How does a judge, who would like to transfer a case, find out which is the competent court of the other Member State?

The European Judicial Atlas in Civil Matters can be used to find the competent court of the other Member State. The Judicial Atlas identifies the territorially competent court in the different Member States with contact details of the different courts (name, telephone, e-mail, etc.) (See Judicial Atlas). The central authorities appointed under the Regulation can also assist the judges in finding the competent court in the other Member State (see Chapter X).

- How should the judges communicate?

Article 15 states that the courts shall co-operate, either directly or through the central authorities, for the purpose of the transfer. It may be particularly useful for the judges concerned to communicate to assess whether in the specific case the requirements for a transfer are fulfilled, in particular if it would be in the best interests of the child. If the two judges speak and/or understand a common language, they should not hesitate to contact each other directly by telephone or e-mail. Other forms of modern technology may be useful, e.g. conference calls. If there are language problems, the judges may rely on interpreters. The central authorities will also be able to assist the judges.

The judges will wish to keep the parties and their legal advisers informed, but it will be a matter for the judges to decide for themselves what procedures and safeguards are appropriate in the context of the particular case.

The courts may also co-operate through the central authorities.

- Who is responsible for the translation of documents?

The mechanisms of translation are not covered by Article 15. The judges should try to find a pragmatic solution which corresponds to the needs and circumstances of each case.

Subject to the procedural law of the State addressed, translation may not be necessary if the case is transferred to a judge who understands the language of the case. If a translation proves necessary, it could be limited to the most important documents. The central authorities may also be able to assist in providing informal translations (see Chapter X). (Practice Guide 2005 p. 19-21)

See also the following scheme:

Cooperation between Member States in case of the placement of a child

in another Member State

The Brussels II Regulation 2003 encourages the central authorities of the different Member States to cooperate in matters of parental responsibility. For this reason a specific Chapter (Chapter IV) is added to the Brussels II Regulation 2003. Article 56 of that last mentioned Chapter deals with the cooperation between the courts of the Member States in situations in which a child is to be placed in another Member State.

‘Where a court having jurisdiction under Articles 8 to 15 contemplates the placement of a child in institutional care or with a foster family and where such placement is to take place in another Member State, it shall first consult the central authority or other authority having jurisdiction in the latter State where public authority intervention in that Member State is required for domestic cases of child placement’ (Article 56(1) BR II 2003). ‘The judgment on placement referred to in paragraph 1 may be made in the requesting State only if the competent authority of the requested State has consented to the placement’ (Article 56(2) BR II 2003). ‘The procedures for consultation or consent referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2 shall be governed by the national law of the requested State’ (Article 56(3) BR II 2003). ‘Where the authority having jurisdiction under Articles 8 to 15 decides to place the child in a foster family, and where such placement is to take place in another Member State and where no public authority intervention is required in the latter Member State for domestic cases of child placement, it shall so inform the central authority or other authority having jurisdiction in the latter State’ (Article 56(4) BR II 2003).