The Brussels II Regulation 2003

Jurisdiction over matters of child abduction

The rules on child abduction (Articles 10, 11, 40, 42, 55)

The fact that jurisdiction over matters of parental responsibility automatically is linked to the child's habitual residence presents the risk of resorting to unlawful action to move the child to another Member State in order to establish artificial jurisdictional links with a view to obtaining custody of a child.

At the international level, the 1980 Hague Convention aims at the restoration of the status quo by requiring the State to which a child has been abducted to order his or her immediate return. The 1980 Hague Convention creates an effective ad hoc remedy without putting in place common rules on jurisdiction, recognition and enforcement. The latter are included in the 1996 Hague Convention, which nonetheless gives precedence to the 1980 Hague Convention. Ultimately both conventions allow under certain circumstances for a transfer of jurisdiction to the Member State to which the child has been abducted once a decision not to return the child has been taken by a court in that State.

The solution put forth in the Brussels II Regulation 2003 is premised on a level of trust inherent in a common judicial area and is expected to produce a deterrent effect, in that it would no longer be possible to bring about a change in the court having jurisdiction through unlawful action. Hence the Member State to which the child has been abducted can only take a provisional measure not to return the child, which could in turn be superseded by a decision on custody taken in the Member State of the child's habitual residence. And unlike the Hague Conventions only on the basis of the latter would jurisdiction be transferred.

The solution relies on the active cooperation between central authorities, which must institute proceedings and keep each other informed of all stages in the process. For purposes of hearing the child, the mechanism of Council Regulation (EC) No 1206/2001 may be used.

Given that a Community-specific solution is fashioned in cases of child abduction, Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 1347/2000 has not been included. Instead, the 1980 Hague Convention is now listed in Article 60 and 62 BR II 2003 among the conventions over which the Regulation takes precedence in the relations between Member States.

This subject is well documented in the Practice Guide 2005, so that the concerning pages of this Guide will be presented here literally.

‘The Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the civil aspects of international child abduction (“the 1980 Hague Convention”), which has been ratified by all Member States, will continue to apply in the relations between Member States. However, the 1980 Hague Convention is supplemented by certain provisions of the Regulation, which come into play in cases of child abduction between Member States. The rules of the Regulation prevail over the rules of the Convention in relations between Member States in matters covered by the Regulation.

The Regulation aims at deterring parental child abduction between Member States and, if such nevertheless take place, ensuring the prompt return of the child to his or her Member State of origin. For the purpose of the Regulation, child abduction covers both wrongful removal and wrongful retention (Article 2(11)). What follows applies to cases both situations.

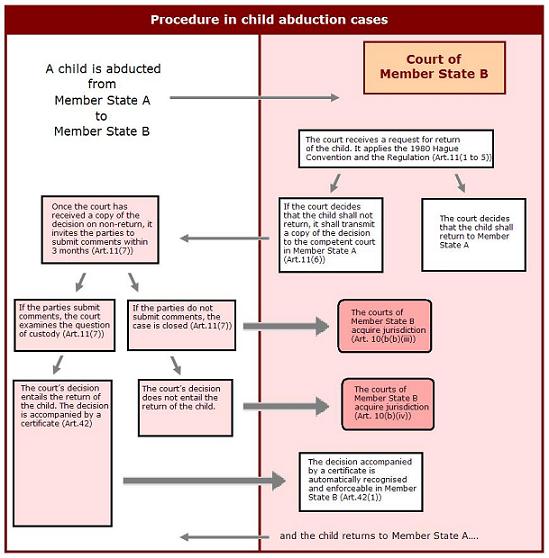

Where a child is abducted from one Member State (“the Member State of origin”) to another Member State (“the requested Member State”), the Regulation ensures that the courts of the Member State of origin retain jurisdiction to decide on the question of custody notwithstanding the abduction. Once a request for the return of the child is lodged before a court in the requested Member State, this court applies the 1980 Hague Convention as complemented by the Regulation. If the court of the requested Member State decides that the child shall not return, it shall immediately transmit a copy of its decision to the competent court of the Member State of origin. This court may examine a question on custody at the request of a party. If the court takes a decision entailing the return of the child, this decision is directly recognised and enforceable in the requested Member State without the need for exequatur. (See flowchart on p. 41)

The main principles of the new rules on child abduction:

1. Jurisdiction remains with the courts of Member State of origin (see chart p. 31).

2. The courts of the requested Member State shall ensure the prompt return of the child (see chart p. 35)

3. If the court of the requested Member State decides not to return the child, it must transmit a copy of its decision to the competent court in Member State of origin, which shall notify the parties. The two courts shall co-operate (see chart p. 40)

4. If the court of the Member State of origin decides that the child shall return,

exequatur is abolished for this decision and it is directly enforceable in the

requested Member State (see chart on p. 40).

5. The central authorities of the Member State of origin and the requested Member State shall co-operate and assist the courts in their tasks.As a general remark, it is appropriate to recall that the complexity and nature of the issues addressed in the various international instruments in the field of child abduction calls for specialised or well-trained judges. Although the organisation of courts falls outside the scope of the Regulation, the experiences of Member States which have concentrated jurisdiction to hear cases under the 1980 Hague Convention in a limited number of courts or judges are positive and show an increase of quality and efficiency’ (Practice Guide 2005, p. 29-30).

Jurisdiction in cases of child abduction (Articles

10, 11, 40, 42, 55)

| Article

10 Jurisdiction in cases of child abduction |

The starting point of Article 10 BR II 2003 is, as a general rule, that the change in a child's habitual residence resulting from abduction should not entail a transfer of jurisdiction to the courts of the Member State to which the child has been abducted. But immediately an exception is made. Article 10 BR II 2003 recognizes that it may be legitimate in certain cases for the de facto situation created by an unlawful act of child abduction to produce as a legal effect the transfer of jurisdiction. To this end, a balance must be struck between allowing the court that is now closest to the child to assume jurisdiction and preventing the abductor from reaping the benefit of his or her unlawful act.

In Article 7 of the 1996 Hague Convention this balance is found on the basis that sufficient time has passed and that no request for return lodged within the one-year period is still pending. This means either that no request for return has been lodged, or that the Member State of this Convention to which the child has been abducted has decided that a valid reason exists for not returning the child by applying one of the exceptions to return of the 1980 Hague Convention.

Whereas the Hague Convention allows for a transfer of jurisdiction on the basis of a decision in the Member State to which the child has been abducted, the Brussels II Regulation allows a transfer of jurisdiction, but only when the abducted child has acquired a habitual residence in another Member States and the strict conditions in Article 10 have been met. The effect is that the left behind parent in the Member State of origin, where the child lived before its abduction, has the opportunity to retain jurisdiction in the Court of origin before jurisdiction shifts to the Member State where the abducted child has acquired a new habitual residence. In line with customary practice within the Hague Conference where the concept of 'habitual residence' has been developed, the term is not defined, but is instead a question of fact to be appreciated by the judge in each case.

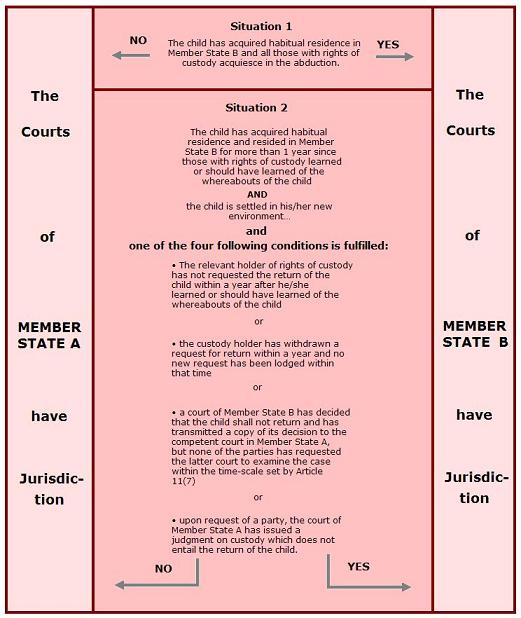

Article 10 of the Regulation states that the Court of the Member State of the new habitual residence has gained jurisdiction when:

- all persons having a right of custody with regard to the abducted child (if necessary this includes the left behind parent in de Member State where the child lived before its abduction) have agreed (acquiesced) that the Member State of the new habitual residence of the child has jurisdiction with regard to the question if the child is abducted and/are should be returned to the person from whom it was taken in the Member State where it lived before its abduction;

- the child has resided in the Member State where it actually lives

for a period of at least one year after the persons with right of custody

has had, or should have had knowledge of the whereabouts of the child

and the child is settled in his/her new environment. But in that case

the jurisdiction only shifts to the court of the Member State of the

new habitual residence when at least one of the following conditions

is met:

(i) Within one year after the holder of rights of custody has had or should have had knowledge of the whereabouts of the child, no request for return has been lodged before the competent authorities of the Member State where the child has been removed or is being retained.

(ii) A request for return lodged by the holder of rights of custody has been withdrawn and no new request has been lodged within the time limit set in paragraph (i) above.

(iii) A case before the Court in the Member State where the child was habitually resident immediately before the wrongful removal or retention has been closed.

(iv) A Judgment on custody that does not entail the return of the child, has been issued by the Courts of the Member State where the child was habitually resident immediately before the wrongful removal or retention.

‘1. Jurisdiction

Article 10

To deter parental child abduction between Member States, Article 10 ensures that the courts of the Member State where the child was habitually resident before the abduction (“Member State of origin”) remain competent to decide on the substance of the case also after the abduction. Jurisdiction may be attributed to the courts of the new Member State (“the requested Member State”) only under very strict conditions (see flowchart p. 31).

The Regulation allows for the attribution of jurisdiction to the courts of the requested Member State in two situations only:Situation 1:

The child has acquired habitual residence in the requested Member State

and

All those with rights of custody have acquiesced in the abduction.OR

Situation 2:

The child has acquired habitual residence in the requested Member State and has resided in that Member State for at least one year after those with rights of custody learned or should have learned of the whereabouts of the child and the child has settled in the new environment and, additionally

at least one of the following conditions is met:

• no request for the return of the child has been lodged within the year after the left behind parent knew or should have known the whereabouts of the child;

• a request for return was made but has been withdrawn and no new request has been lodged within that year;

• a decision on non-return has been issued in the requested State and the courts of both Member States have taken the requisite steps under Article 11(6), but the case has been closed pursuant to Article 11(7) because the parties have not made submissions within 3 months of notification;

• the competent court of origin has issued a judgment on custody which does not entail the return of the child’ (Practice Guide 2005, p. 30-31).

or

See also scheme:

A child is abducted from Member State A to Member State B. Which court

has jurisdiction to decide on the substance of the matter?

Rules to ensure the prompt return of the child

The 1980 Hague Convention tries to secure the fast return of children who are wrongfully removed to or retained in any Contracting State and to ensure that rights of custody and of access under the law of one Contracting State are effectively respected in the other Contracting States. The Contracting States shall take all appropriate measures to secure within their territories the implementation of the objects of the 1980 Hague Convention. For this purpose they shall use the most expeditious procedures available. Every Contracting State has designated a Central Authority to discharge the duties which are imposed by the Convention upon such authorities. Federal States, States with more than one system of law or States having autonomous territorial organizations are free to appoint more than one Central Authority and to specify the territorial extent of their powers. Where a State has appointed more than one Central Authority, it has to designate the Central Authority to which applications may be addressed for transmission to the appropriate Central Authority within that State.

If a child has been abducted and removed to another Contracting State or is retained there unlawfully, then under the 1980 Hague Convention any person, institution or other body, claiming that a child has been removed or retained in breach of custody, may apply either to the Central Authority of the State where the child had its habitual residence prior before its abduction or to the Central Authority of any other Contracting State, for instance the Contracting State where the child actually stays, for assistance in securing the return of the child. A request to order the return of the child to a person in another Contracting State can be filed at the courts of the Contracting State where the abducted child actually is present. The requirements to be met by an applicant for a return order are strict. He must establish that the child was habitually residing in the other Contracting State, that the removal or retention of the child constituted a breach of custody rights attributed by the law of that State and that the applicant was actually exercising those rights at the time of the wrongful removal or retention.

The Brussels II Regulation 2003 refers in these situations to the procedure under the 1980 Hague Convention. ‘Where a person, institution or other body having rights of custody applies to the competent authorities in a Member State to deliver a judgment on the basis of the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (hereinafter ‘the 1980 Hague Convention'), in order to obtain the return of a child that has been wrongfully removed or retained in a Member State other than the Member State where the child was habitually resident immediately before the wrongful removal or retention, paragraphs 2 to 8 [of Article 11] shall apply (Article 11(1) BR II 2003).

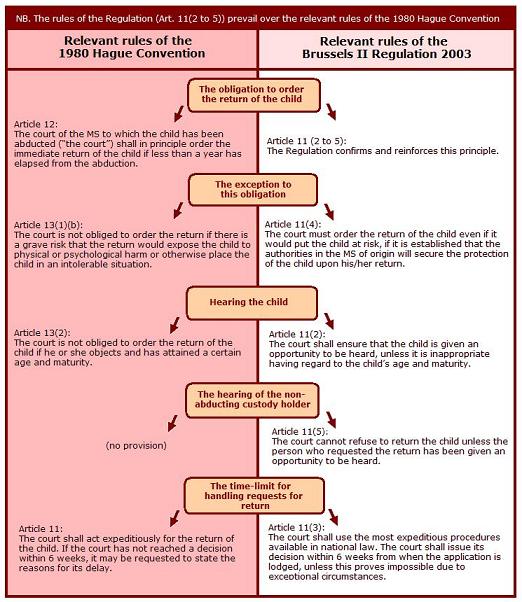

The rules in Article 11 BR II 2003 are addressed to the courts of the Member State where the abducted child actually stays. Such a court, after receiving a request to order the return of a child of an applicant, must determine whether such an order has to be given or not in view of the appropriate rules of the 1980 Hague Convention and the Brussels II Regulation 2003. It must decide in accordance with a strict procedure. It has to act expeditiously in proceedings on the application, using the most expeditious procedures available in national law. The court shall, except where exceptional circumstances make this impossible, issue its judgment no later than six weeks after the application is lodged (Article 11(3) BR II 2003). It has to ensure that the child is given the opportunity to be heard during the proceedings unless this appears inappropriate having regard to his or her age or degree of maturity. The court cannot refuse to return a child if it has established that adequate arrangements have been made to secure the protection of the child after his or her return to the other Member State. If it wants to refuse to return the child, it firstly must give the person who requested the return of the child an opportunity to be heard.

The Practice Guide 2005 makes the following comment to this subject:

‘Article 11(1)-(5)

When a court of a Member State receives a request for the return of a child pursuant to the 1980 Hague Convention, it shall apply the rules of the Convention as complemented by Article 11(1) to (5) of the Regulation (see flowchart p. 35). To this end, the judge may find it useful to consult the relevant case-law under this Convention which is available at the INCADAT database set up by the Hague Conference on Private International Law. The explanatory report and the Practice Guides concerning this Convention can also be of use (see website of the Hague Conference on Private International Law).

2.1. The court shall assess whether an abduction has taken place under the terms of the Regulation (Article 2(11)(a),(b))

The judge shall first determine whether a “wrongful removal or retention” has taken place in the sense of the Regulation. The definition in Article 2(11) is very similar to the definition of the 1980 Hague Convention (Article 3) and covers a removal or retention of a child in breach of custody rights under the law of the Member State where the child was habitually resident before the abduction. However, the Regulation adds that custody is to be considered to be exercised jointly when one of the holders of parental responsibility cannot decide on the child’s place of residence without the consent of the other holder of parental responsibility. As a result, a removal of a child from one Member State to another without the consent of the relevant person constitutes child abduction under the Regulation. If the removal is lawful under national law, Article 9 of the Regulation may apply.2.2. The court shall always order the return of the child if he or she can be protected in the Member State of origin (Article 11(4))

The Regulation reinforces the principle that the court shall order the immediate return of the child by restricting the exceptions of Article 13(b) of the 1980 Hague Convention to a strict minimum. The principle is that the child shall always be returned if he/she can be protected in the Member State of origin.

Article 13(b) of the 1980 Hague Convention stipulates that the court is not obliged to order the return if it would expose the child to physical or psychological harm or put him/her in an intolerable situation. The Regulation goes a step further by extending the obligation to order the return of the child to cases where a return could expose the child to such harm, but it is nevertheless established that the authorities in the Member State of origin have made or are prepared to make adequate arrangements to secure the protection of the child after the return.

The court must examine this on the basis of the facts of the case. It is not sufficient that procedures exist in the Member State of origin for the protection of the child, but it must be established that the authorities in the Member State of origin have taken concrete measures to protect the child in question.

It will generally be difficult for the judge to assess the factual circumstances in the Member State of origin. The assistance of the Central Authorities of the Member State of origin will be vital to assess whether or not protective measures have been taken in that country and whether they will adequately secure the protection of the child upon his or her return. (see chapter X).2.3. The child and the requesting party shall have the opportunity to be heard (Article 11(2),(5))

The Regulation reinforces the right of the child to be heard during the procedure. Hence, the court shall give the child the opportunity to be heard unless the judge considers it inappropriate due to the child’s age and degree of maturity. (See chapter IX).

In addition, the court cannot refuse to return the child without first giving the person who requested the return the opportunity to be heard. Having regard to the strict time-limit, the hearing shall be carried out in the quickest and most efficient manner available. One possibility is to use the arrangements laid down in Regulation (EC) No 1206/2001 on cooperation between the courts of the Member States in taking of evidence in civil or commercial matters (“the Evidence Regulation”). This Regulation, which applies as of 1 January 2004, facilitates the co-operation between courts of different Member States in the taking of evidence in e.g. family law matters. A court may either request the competent court of another Member State to take evidence or take evidence directly in the other Member State. Given that the court must decide within 6 weeks on the return of the child, the request must necessarily be executed without any delay, and considerably within the general 90 days time limit, prescribed by Article 10(1) of the Evidence Regulation. The use of video-conference and tele-conference, which is proposed in Article 10(4) of the above Regulation, could be particularly useful to take evidence in these cases.2.4. The court shall issue a decision within a six-week deadline (Article 11(3))

The court must apply the most expeditious procedures available under national law and issue a decision within six weeks from being seised with the request (…). This time limit may only be exceeded if exceptional circumstances make it impossible to respect.

With regard to decisions ordering the return of the child, Article 11(3) does not specify that such decisions, which are to be given within six weeks, shall be enforceable within the same period. However, this is the only interpretation which would effectively guarantee the objective of ensuring the prompt return of the child within the strict time limit. This objective could be undermined if national law allows for the possibility for appeal of a return order and meanwhile suspends the enforceability of that decision, without imposing any time-limit on the appeal procedure. For these reasons, national law should seek to ensure that a return order issued within the prescribed six week time-limit is “enforceable”. The way to achieve this goal is a matter of national law. Different procedures may be envisaged to this end, e.g.:

(a) National law may preclude the possibility of an appeal against a decision

entailing the return of the child, or

(b) National law may allow for the possibility for appeal, but provide that a decision entailing the return of the child is enforceable pending any appeal.

(c) In the event that national law allows for the possibility of appeal, and suspends the enforceability of the decision, the Member States should put in place

procedures to ensure an accelerated hearing of the appeal so as to ensure the

respect of the six-week dead-line.

The procedures described above should apply mutatis mutandis also to non-return orders in order to minimise the risk of parallel proceedings and contradictory decisions. A situation could otherwise arise where a party appeals against a decision on non-return that is issued just before the six weeks deadline elapses and at the same time requests the competent court of origin to examine the case (Practice Guide 2005, p. 33 – 35).

See also scheme

The requested court decides that the child shall not return (Article 11(6)(7)(8))

From the previous rules follows that the court of the Member State where the abducted child actually is staying, has to consider whether it orders the return of the abducted child to the Member State where it lived earlier or not. Of course, in exceptional cases it’s possible that it decides that a return of the child is not appropriate. Article 11(6) BR II 2003 makes clear which formalities it has to live up to in such a case.

If a court has issued an order on non-return pursuant to Article 13 of the 1980 Hague Convention, the court must immediately either directly or through its Central Authority, transmit a copy of the court order on non-return and of the relevant documents, in particular a transcript of the hearings before the court, to the court with jurisdiction or central authority in the Member State where the child was habitually resident immediately before the wrongful removal or retention, as determined by national law. The court shall receive all the mentioned documents within one month of the date of the non-return order (Article 11(6) BR II 2003).

Even if the court of the Member State to which the child has been abducted does not order the return of a child under Article 13 of the Hague Convention, the court of the child's original habitual residence can still order the child to be returned. ‘Notwithstanding a judgment of non-return pursuant to Article 13 of the 1980 Hague Convention, any subsequent judgment which requires the return of the child issued by a court having jurisdiction under this Regulation shall be enforceable in accordance with Section 4 of Chapter III below in order to secure the return of the child’ (Article 11(8) BR II 2003).‘The competent court shall transmit a copy of the decision on non-return to the competent court in the Member State of origin.

Having regard to the strict conditions set out in Article 13 of the 1980 Hague Convention and Article 11(2) to (5) of the Regulation, the courts are likely to decide that the child shall return in the vast majority of cases. However, in those exceptional cases where a court nevertheless decides that a child shall not return pursuant to Article 13 of the 1980 Hague Convention, the Regulation foresees a special procedure in Article 11(6) and (7).

This requires a court which has issued a decision on non-return to transmit a copy of its decision together with the relevant documents to the competent court in the Member State of origin. This transmission can take place either directly from one court to another, or via the central authorities in the two Member States. The court in the Member State of origin is to receive the documents within a month of the decision on non-return.

The court of origin shall notify the information to the parties and invite them to make submissions, in accordance with national law, within three months of the date of notification, to indicate whether they wish that the court of origin examines the question of custody of the child. If the parties do not submit comments within the three month time-limit, the court of origin shall close the case. The court of origin shall examine the case if at least one of the parties submits comments to that effect. Although the Regulation does not impose any time-limit on this, the objective should be to ensure that a decision is taken as quickly as possible.To which court shall the decision on non-return be transmitted?

The decision on non-return and the relevant documents shall be transferred to the court which is competent to decide on the substance of the case. If a court in the Member State has previously issued a judgment concerning the child in question, the documents shall in principle be transmitted to that court. In the absence of a judgment, the information shall be sent to the court which is competent according to the law of that Member State, in most cases where the child was habitually resident before the abduction. The European Judicial Atlas in Civil Matters can be a useful tool to find the competent court in the other Member State (Judicial Atlas). The central authorities appointed under the Regulation can also assist the judges in finding the competent court in the other Member State (see chapter IX).Which documents shall be transmitted and in which language?

Article 11(6) provides that the court which has issued the decision on non-return shall transmit a copy of the decision and of the “relevant documents, in particular a transcript of the hearings before the court”. It is for the judge who has taken the decision to decide which documents are relevant. To this end, the judge shall give a fair representation of the most important elements highlighting the factors influencing the decision. In general, this would include the documents on which the judge has based his or her decision, including e.g. any reports drawn up by social welfare authorities concerning the situation of the child. The other court must receive the documents within one month from the decision.

The mechanisms of translation are not governed by Article 11(6). Judges should try to find a pragmatic solution which corresponds to the needs and circumstances of each case. Subject to the procedural law of the State addressed, translation may not be necessary if the case is transferred to a judge who understands the language of the case. If a translation proves necessary, it could be limited to the most important documents. The central authorities may also be able to assist in providing informal translations. If it is not possible to carry out the translation within the one month time limit, it should be carried out in the Member State of origin’ (Practice Guide 2005, p. 37-38).

‘The abolition of exequatur for a decision of the court of origin entailing the return of the child (Articles 40, 42)

As described above (….), a court that is seised with a request for the return of a child pursuant to the 1980 Hague Convention shall apply the rules of the Convention as complemented by Article 11 of the Regulation. If the requested court decides that the child shall not return, the court of origin will have the final say in determining whether or not the child shall return.

If the court of origin takes a decision that entails the return of the child, it is important to ensure that this decision can be enforced quickly in the other Member State. For this reason, the Regulation provides that such judgments are directly recognised and enforceable in the other Member State provided they are accompanied by a certificate.

The consequence of this new rule is two-fold: (a) it is no longer necessary to apply for an “exequatur” and (b) it is not possible to oppose the recognition of the judgment. The judgment shall be certified if it meets the procedural requirements (….).

The judge of origin shall issue the certificate by using the standard form in Annex IV in the language of the judgment. The judge shall also fill in the other information requested in the Annex, including whether the judgment is enforceable in the Member State of origin at the time it is issued.

The court of origin shall in principle deliver the certificate once the judgment becomes “enforceable”, implying that the time for appeal shall, in principle, have elapsed. However, this rule is not absolute and the court of origin may, if it considers it necessary, declare that the judgment shall be enforceable, notwithstanding any appeal. The Regulation confers this right on the judge, even if this possibility is not foreseen under national law. The aim is to prevent dilatory appeals from unduly delaying the enforcement of a decision’ (Practice Guide 2005, p. 40).

The court of origin rules on all rights of custody

and access and/or the return of the child (Articles 11 (7) and 42)

When the court of the Member State where the abducted child actually stays, has refused to order the return of the child to the Member State where the child previously had its habitual residence, then this has in principle no effect on the jurisdiction over matters relating to the custody of the child. This jurisdiction is still based on Article 10 BR II 2003. The court of origin has and keeps jurisdiction over matters relating to parental responsibility, unless jurisdiction has shifted in accordance with Article 10 to the courts of the Member State where the child actually stays.

If the court of origin was already seised by one of the parties, it informs both parties of the refusal of the court of the other Member State to order the return of the abducted child. If the party, who applied for the return of the child, did not yet seised the court of origin, then the Central Authority of that State notifies the parties that the request to order the return of the child has been denied. The court of origin or the Central Authority also must invite both parties to make submissions to the court of origin, in accordance with national law, within three months of the date of notification so that the court can examine the question of custody of the child. Without prejudice to the rules on jurisdiction contained in this Regulation, the court shall close the case if no submissions have been received by the court within the time-limit.

But when both parties or one of them asks the court of origin within the time-limit to rule on a matter of custody or access, it has full jurisdiction, in the sense that it’s competent to deal with the substance of the case in its entirety (Article 11(7) BR II 2003).

‘Its jurisdiction is therefore not limited to deciding upon the custody of the child, but may also decide for example on access rights. The judge should, in principle, be in the position that he or she would have been in if the abducting parent had not abducted the child but instead had seised the court of origin to modify a previous decision on custody or to ask for a authorisation to change the habitual residence of the child. It could be that the person requesting return of the child did not have the residence of the child before the abduction, or even that that person is willing to accept a change of the habitual residence of the child in the other Member State provided that his or her visiting rights are modified accordingly’ (Practice Guide 2005, p. 38).

The court of origin can even give a judgment which indicates that the abducted child still has to be returned to his parents or custodians in the Member State where the child had its habitual residence prior to his abduction and taking away to another Member State.

The court of origin should apply certain procedural rules when examining the case. Compliance with these rules will later allow the court of origin to deliver the certificate mentioned in Article 42(2) BR II 2003. The court of origin should ensure that (a) all parties are given the opportunity to be heard, (b) the child is given an opportunity to be heard, unless a hearing is considered inappropriate having regard to the age and maturity of the child and (c) its judgment takes into account the reasons for and evidence underlying the decision on non-return. These formalities can cause a number of practical problems, since the parent and the child, who both are staying in another Member State, will not always want to return to the Member State of the court of origin, not even to be heard.

The Practice Guide 2005 (p. 39 – 41) suggests that these problems have to be solved by interference of the courts in the involving Member States:

‘Certain practical aspects

How can the judge of origin take account of the reasons underlying the decision on non-return?

It is necessary to establish cooperation between the two judges in order for the judge of origin to be able properly to take account of the reasons for and the evidence underlying the decision on non-return. If the two judges speak and/or understand a common language, they should not hesitate to make contact directly by telephone or e-mail for this purpose. If there are language problems, the central authorities will be able to assist (see Chapter X).How will it be possible to hear the abducting custody holder and the child if they stay in the other Member State?

The fact that the abducting custody holder and the abducted child are not likely to travel to the Member State of origin to attend the proceeding requires that their evidence can be given from the Member State where they find themselves. One possibility is to use the arrangements laid down in Regulation (EC) No 1206/2001 (“the Evidence Regulation”). This Regulation, which applies as of 1 January 2004, facilitates the co-operation between courts of Member States in the taking of evidence in e.g. family law matters. A court may either request the competent court of another Member State to take evidence or take evidence directly in that other Member State. The Regulation proposes the taking of evidence by means of video-conference and tele-conference.

The fact that child abduction constitutes a criminal offence in certain Member States should also be taken into account. Those Member States should take the appropriate measures to ensure that the abducting custody holder can participate in the court proceeding in the Member State of origin without risking criminal sanctions. Again a solution could be found by using the arrangements laid down in the Evidence Regulation.

Another solution could be put in place special arrangements to ensure the free passage to and from the Member State of origin to facilitate the personal participation in the procedure before the court of that State of the individual who abducted the child.

If the court of origin takes a decision that does not entail the return of the child, the case is to be closed. Jurisdiction to decide on the question of substance is then attributed to the courts of the Member State to which the child has been abducted (see flowcharts p. 35 and 41).

If, on the other hand, the court of origin takes a decision which entails the return of the child, that decision is directly recognised and enforceable in the other Member State provided it is accompanied by a certificate (see point 5 and flowchart p. 41)’.

See also the following Scheme