Legal System of Civil Law in the Netherlands

To understand the law, you first have to approach the law as a lawyer

would, and this, of course, from the perspective of a civil law system,

since the private law of the Netherlands is grafted upon Roman-Germanic

law. The law consists of nothing more then a large number of rules of

behaviour (or rules of conduct). The law, in other words, is just a set

of appointments between all people ordering how to behave with regard

to what they consider to be correct and fair. In the past people made

these rules themselves. That today is no longer possible. For this reason

the people of a society have transferred this competence to the government,

which establishes and maintains these rules for them. In a modern democracy

the people can only elect once in a few years the members of Parliament,

the Municipality Council and other public bodies. These members together

influence the acting and organisation of the government. The various institutions

of the government decide, each on their own legal and geographical territory,

which rules are issued, how they work in practice and how they are or

have to be interpreted in the case of a dispute. Legislation, implementation

and jurisdiction are these days an exclusive task of the government. The

government is the only institute in society that is allowed to use violence

to enforce the compliance with its rules. This violence expresses itself

in imposing a fine or a prison sentence, that sometimes even can lead

to the death of the one who has broken a rule. No other person is allowed

to use violence to get his way. The people of a country are submitted

to the rules of the government because they have agreed upon this themselves.

It’s the only way to prevent chaos and to impede that the strongest

and most aggressive persons can take 'the law' into their own hands. Other

criteria than random violence must ascertain whether someone is damaged

in his interests and, because of this, has the right to claim a certain

behaviour from another person. These criteria are retrieved in the law,

which takes into account everybody's interest and the interest of the

society as a whole. The starting point of the law is always what is reasonable

and fair, given all circumstances.

The law as a collection of rules of behaviour

The law exists of a large number of binding appointments that have to be observed by everyone. Those appointments have been laid down in laws. They regulate how persons must behave mutually and what they can expect from each other, for example with respect to their property or to what other persons may or may not do. A rule of law is a right or duty that is recognised as such by law. This means that the right or duty finds its basis in law, so that the government can enforce the compliance with it, if necessary with the assistance of judicial authorities and the police. With this, the rules of law distinguish themselves from other rules of conduct, which for example result from decorum, religion or morality.

Rules of law are rules of conduct. The law of a State consists of all the rules of behaviour that people within that society have agreed upon in order to regulate their mutual relations, as well to each other as to property and other objects. But in contrast to other rules that prescribe a certain behaviour, the rules of law are enforceable.

Religious rules of behaviour are imposed by a not perceptible higher power. They can be subdivided into two types. On the one hand in rules of behaviour which indicate what is right and what is wrong (you are not allowed to kill another person, you will not commit adultery). On the other hand there are standards which specifically stipulate how a religion must be confessed. These rules of behaviour differ of course according to the religion in question. One religion stipulates for example that one must make the sign of the cross when praying, the other that you must kneel towards Mecca.

Besides religion also morality has always influenced the behaviour of people. Moral rules of behaviour are not coming from a higher power, like a God, such as religious rules do. They are accepted by society as the dominating way to think. Of course, people should behave accordingly. The widely accepted conception that people are equal or that parents must take care for their children, is a rule of morality or, if you want, ethics. Moral rules change in course of time. Not so long ago it was by no means commonly accepted that people of every race or sexual disposition were equal.

Rules of decorum contain the good manners in the broadest sense of the word. The boy in the bus who cedes his seat to an older lady or the man who raises his hat when greeting a friend act in compliance with decorum. The behaviour of these gentlemen is dictated by what society regards as the correct way to do in such circumstances.

Also the law tries to influence human behaviour in a certain way. But in what do rules of law differ from other rules of behaviour? The answer must be: ‘in fact only in their enforceability’. Characteristic for rules of behaviour issued by the government, is that everyone has to obey them and that the government can en will enforce the compliance with these rules, if need be, by exercising violence. Everyone who breaks the law, no matter who, must pay a fine or has to suffer another punishment, like a prison sentence. In this way the observance of a rule of law is guaranteed. The other rules of behaviour have no means of punishment that apply to everyone. There is neither a central institute that can check and enforce the observance of the rule of behaviour. He who breaks rules of decorum only needs to fear reprobate responses from his surroundings. He who acts contrary to morality possibly is touched by a sting of conscience. He who violates a religious rule can awaken the rage of God or the aversion of the members of a religious community. These sanctions aren’t concrete at all. Many shrug thus their shoulders. Such rules of behaviour have no effect on them. They don't influence their behaviour, nor their decisions how to live and act. The law, however, knows how to force people to behave in a certain way and is able to implement it. It doesn’t resign when a rule is broken, but tries to hurt the offender at his most sensitive spot (personal freedom, property, financial situation), to secure the observance of its rules. In some countries persons who have committed a serious crime can even pay for it with their lives. But in the Netherlands the death penalty doesn’t exist anymore.

The law is subdivided in several areas that regulate various kinds of relationships between different persons. Criminal law, for example, controls the relationship between the government and citizens who have committed a crime or an indictable offence (felony). Administrative law gives rules which settle the relationship between the government and citizens concerning public matters. Civil law regulates relationships between citizens mutually, for instance those which come from a family connection or marriage. This includes the law of matrimonial property and inheritance. Furthermore it sets rules for legal entities, like limited private companies (Ltd.), associations and foundations. But most of all, civil law arranges the way citizens are entitled to existing property and how property rights may arise and can be delimited of that of others. This part is called the law of valuable rights (‘droit patrimonial’) and includes property law and the law of contracts and obligations.

In the Netherlands civil law is mainly regulated in the Civil Code, named ‘Burgerlijk Wetboek’ (BW). This code has been renewed in 1992 and is now one of the most modern codes on the field of civil law in Europe.

Valuable rights (‘droit patrimonial’)

The field of civil law that is indicated with the French words 'droit patrimonial' ('vermogensrecht') regulates the relationships of people to assets and financial based relationships between private persons. The rights that are set by this field of law are called patrimonial rights ('vermogensrechten'). All rights with a certain value are patrimonial rights. For this reason these rights will be named 'valuable rights' on this internet site, because it makes clear immediately what really is meant. Article 3:6 DCC defines valuable rights as rights which can be transferred or which intend to give its proprietor material benefit or which have been given in exchange for material benefit that has already been given or will be given in future. Rights in rem (ownership, easement, long leasehold, apartment right, right of superficies, pledge, mortgage) and rights in personam (debt-claims) are valuable rights. The same goes for intellectual property rights (copyrights, trade marks, patents), which however aren't the subject of this internet site.

The relationship between a person and an asset is called a ‘property right’. In principle the law specifies which powers and possibilities the proprietor of a property right has with regard to the asset to which his property right is attached. Property rights are elaborated in the Civil Code of the Netherlands, which not only describes what the entitled person may do with a specific asset, but also how he can defend himself against other persons who disturb him in exercising his rights to that asset. These powers only exist because the law says so.

A financial based relationship between two persons is usually an obligation. A debt-claim of a person against another person with regard to a certain performance, which claim forms a part of the obligation, is in itself an asset that belongs to someone and that can be encumbered with a limited property right.

It’s important to recognise that also with regard to the law of valuable rights, and therefore in property law, the rules only indicate a certain behaviour or prohibit persons to act in a specific way. Even property law consists solely of a large number of binding appointments that have to be observed by everyone. Those appointments have been laid down in laws. They regulate how persons must behave mutually and what they can expect from each other, for example with respect to an asset or to a promise to perform something. A valuable right represents in this sense a bundle of powers to an asset or to a performance, recognised as such by law. This means that the right to execute these powers finds its basis in law, so that the entitled person has the possibility to enforce the observance of his valuable right, if need be, with the help of judicial authorities and the police force. Again it is to be mentioned that a valuable right is not a visible or tangible thing, which can be touched or even picked up. Every legal right, thus also a valuable right or property right, is – as a rule of behaviour - invisible, therefore incorporeal, although it may include certain rights of use and exclusive powers to an asset that in itself is tangible, for example to a car or a house. Nevertheless the right of ownership to that car is incorporeal, since it’s just a rule of behaviour which is recognized by law as a legal rule that has to be observed by everyone, including the owner.

Opposite to the valuable right of the proprietor (entitled person), there is always a legal duty of one or more other persons. A legal duty can be defined as every duty that the law imposes upon a person. Because it’s a duty that is labelled as such by law, the person who is charged with it, can be forced to comply with it. If he doesn’t meet his duties, he will be condemned to pay for damages or he might receive another punishment. With authorisation of the court, the police can put him in jail or take the chargeable performance of him, which may even result in a public sale of his properties. The person whose valuable right has been violated, is compensated in this way. In this respect a legal duty differs from a duty imposed by religion, decorum or morality. Depending on the nature of the valuable right, it's possible that the whole world has to respect the rights and powers of its proprietor (rights in rem) or that just one person or one specific group of persons has to observe them (rights in personam).

Property rights lay a fictitious connection between a person on the one hand and an object on the other. Dutch law only accepts natural persons (humans) and legal entities as persons to whom a property right may belong. Animals, plants and other things are not accepted as persons. They can't own, posses or hold property rights. In fact, they themselves are objects to which a property right can be linked.

A property right can be related to several objects. In property law the object is usually a thing (movable or immovable tangible object) or a performance to be fulfilled by another person. The property right stipulates within this relationship which powers its proprietor has in relation to that object. It also explains to what extent other persons have to respect these powers of the proprietor over that object. In this way every property right can be analysed up to a number of intangible, though enforceable rules of behaviour concerning a specific object, which rules have to be observed by the proprietor of the property right as well as by all other people.

This theoretical explanation can be clarified with an example. The starting point is the most important property right in Dutch civil law: the right of ownership, which in the Netherlands can only be attached to a movable or immovable thing.

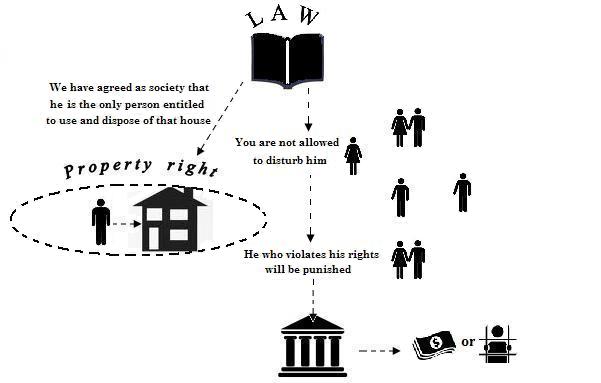

What does it really mean when one says that Peter is the owner of a house that is situated at Churchstreet 20 in the city of Eindhoven. One might answer: ‘that it’s his house’, ‘that he can call it his own'. That’s correct of course, but then one approaches the property from the normal point of view. To understand the legal meaning of this sentence, one must look a bit further. When it is stated that Peter is the owner of a house at Churchstreet 20 in Eindhoven, it actually means that Peter under civil law is entitled to exercise all the powers with respect to this house insofar civil law grants these rights and powers to a person who has obtained a right of ownership in agreement with the law. If one analyses this further, the next picture arises. Civil law first describes what the content of the right of ownership in general is, therefore which powers a random owner of property normally has. It stipulates, in addition, that Peter has acquired such a right of ownership of the house, since he has met the requirements as set by civil law in order to get a property right that is recognized as a right of ownership. From the previous rules, two other rules result. First, that all other persons must withhold themselves from behaviour that could disturb the owner - this is Peter - in exercising his powers over the house. Peter must always be able to use the house in conformity with the powers he has according to his right of ownership; no other person is allowed to take these powers from him. Secondly, the previous rules make clear that Peter is able to enforce that everyone has to recognize and observe his legal position, if necessary by asking the court and police for assistance. The right of ownership includes in that sense a number of rules of behaviour which stipulate on the one hand what Peter can do with the house and on the other hand what all other persons may and may not do with respect to that same house. The law only consists of invisible and intangible, but nevertheless enforceable rules of behaviour.

Enforceable legal arrangements regarding property

rights in a thing

(right of ownership of a house)

Similar to this, property rights to other objects than tangible things

can be analysed. Again an example, but now by means of the most important

property right to a performance: the debt-claim of a creditor against

his debtor.

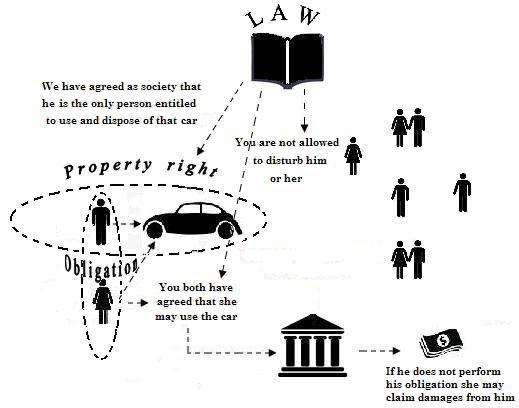

When one says that John is entitled to a performance that William has to fulfil, this doesn’t mean that John has a property right in William himself. That’s not possible, because property rights, like the debt-claim of a creditor, can only be attached to certain objects, not to persons. If one says that John has a debt-claim against William, this means that John can demand from William that he carries out the performance to which he has engaged himself and that, if he doesn’t perform it, John may enforce his debt-claim or, where this is impossible, demand a compensation for damages. The debt-claim reflects within this relationship what creditor John according to civil law may expect in general of his debtor William and which measures he can take if William doesn’t satisfy his debt properly. The content of John’s debt-claim is defined by civil law. Civil law specifies how the creditor and debtor have to behave towards each other with respect to the object of the property right of the creditor - i.e. the claim to the performance of the debtor. The fact that the law recognises the debt-claim of the creditor as a valuable right, means that the creditor, who is entitled to this performance, is able to enforce the compliance with it.

Enforceable legal arrangements regarding obligations

(debt-claim to use a car)

From the examples and schemes above it becomes clear once more that the

law is nothing else than the sum of thousands of rules of behaviour (appointments)

that must be observed by everyone. When everyone feels and acts as if

these rules represent the reality, then these rules automatically become

reality, at least the legal reality. The government ensures that this

fiction is kept alive. What the content of these legal rules is and which

powers the entitled persons have, is told by civil law. The law also indicates

which kind of property rights can arise, how the proprietor may get such

rights, how he can transfer them to another person and how they will end.

It’s the job of a lawyer to understand and work with these rules.

He studies the law to retrieve how different relationships are regulated

by law and what the impact is of these rules in a concrete situation.

If required, he makes sure that the legal position of his client, as recognised

by law, will hold. He may even start legal proceedings in court to get

a judgement in favour of his client, with which he can order a bailiff

or the police to repair the situation in conformity with the law.

end